My general sense is that Brazilian music exists in the North American imagination almost purely by way of caricatures. Most prominently we think of Carmen Miranda in the 1940s and her tutti frutti hat

or take the famous elevator music (muzak) scene from “The Blues Brothers” (John Landis, 1980), featuring Jobim and Moraes’ near ubiquitous 1964 hit “The Girl from Ipanema”

Both of these caricatures function to create a myth of Brazil as a land of plenitude and pleasure: they have so many bananas they wear them as hats! It’s so relaxed there, the music will lull you sweetly into a tranquil midday nap on the beach!

The drummer/percussionist Airto Moreira leaned into this caricature for his track “The Happy People,” featured on the saxophonist Cannonball Adderley’s album celebrating Brazilian music of the same name from 1972:

The caricature reaches its full flowering by way of Terry Gilliam’s bitingly dark, dystopian 1985 film “Brazil”

Gilliam’s “Brazil” prominently features Ary Barroso’s 1939 hit composition “Aquarela do Brasil [Watercolor of Brazil],” popularly known in the English-speaking world simply as “Brazil.” Stuck in an ugly dystopian, techno-bureaucratic surveillance state, Jonathan Pryce’s character Sam Lowry fantasizes about a life of easy pleasures: beautiful vistas, cheap heroism, and the readily available girl of his dreams.

The song plays two ways in the film, overdetermining the caricature: first, as a kind of call to an alternative life, one of plenitude and pleasure, with the happy people. Second, however, the song itself, with its light, happy, propulsive melody and constant melodic repetition (both within itself and in the film) recalls the thin, happy veneer muzak paints on the modern working life: the cheerful, but idiotic co-worker; the tedium of repetitive, mundane tasks.

Suffice to say, the caricature, misses the mark. (We need hardly mention here that this colonial exoticization is hardly exclusive to Brazil and pervades the English-speaking engagement with most Latin and/or World music.) The cultural touchstone for most rock fans, is Brazil’s Tropicalia movement (roughly 1967-1972), which tracks alongside the cultural revolutions in the late 1960s in North America and Europe. In the context of Brazil, the cultural revolution functioned as a reaction to the political and cultural realities of the day (Brazil’s leftist democratically elected government was overthrown by a CIA-backed coup d’état in 1964; from 1959-1967 Brazilian pop music was dominated by the sweet, tranquil sounds of Bossa Nova). The explosion of Tropicalia, with its vibrant, complex, and avant-garde melodies, is evident from the start as a rejection of the contemporary political/cultural order. Compare two Caetano Veloso tracks from the period by way of example to dramatize the shift in sensibilities.

First, from his 1967 Bossa Nova album Domingo, released with Gal Costa

Second, from his 1968 self-titled album, announcing the birth of Tropicalia

Brazilian pop music is incredibly diverse. Its musicians, bursting with talent and experimentation, relentlessly borrow from and reinterpret the past. This can most clearly be seen in the Música popular brasileira (MPB) movement of the late 1960s through the 1970s. Rather than tunneling in one direction to create a unique, easily identifiable, and easily repeatable sound (like Samba, Bossa Nova, or Tropicalia), MPB incorporates bits and pieces of everything into a new whole. The pinnacle achievement in this regard is the 1972 collaboration album by Milton Nascimento and Lô Borges “Clube da Esquina”

The album cover itself tells something of the complicated colonial and cultural history of Brazil, two boys (one white, one black) sit together on a dirt road outside Rio, barbed wire noticeably in picture. The album is a sprawling work of creativity, a masterpiece.

The Breakdown

What follows is not intended to be a canonical, or authoritative history of Brazilian music. Far from it. Rather, it is a highly idiosyncratic look at a fairly broad cross-section of Brazilian music that I really like.

I owe my love of Brazilian music to the influence of an old high school friend, who now makes violins in France (true story!), who himself found it, if I remember correctly, by way of David Byrne’s Luaka Bop releases. I dedicate this Summer to him, and hope he finds something new and interesting to listen to in one of the many playlists that follow.

As a way of orienting ourselves, I’ll be breaking down Brazilian pop music into 4 broad categories:

- The Guitar Folks (for our purposes, 1940s through 1980s)

- Bossa Nova (1959-1967 and beyond)

- Tropicalia (1967-1972)

- Música popular brasileira (MPB) (late 60s onward)

Because I’m lousy at editing myself… I’ve created 6 playlists for this Summer (one for each section above and a master list containing everything). For those looking for an easy introduction, here’s a broad overview of the hits:

In what follows, each section will have its own playlist for those looking to dive deeper, and one playlist combining everything, for those, like me, wanting it all.

The Guitar Folks

Perhaps it’s because I play guitar (badly), but for me the anchor instrument for all Brazilian music is the guitar. Starting early in the 20th Century, we can trace the development of Brazilian music through the guitar in figures like

- Cartola, and his guitar-based Samba compositions

- Garoto, and his guitar-based Choro compositions (a kind of analogue to the bluesy ballads of Portuguese Fado music)

- Luiz Bonfá, João Gilberto, Jobim, Baden Powell, and the development of Bossa Nova centered around the guitar

- Os Mutantes, Caetano Veloso, Tom Zé, Gilberto Gil, Jorge Ben, Gal Costa, etc., and the development of Tropicalia with its introduction of the electric guitar (occasionally at its most shrill)

- Tim Maia, Erasmo Carlos, Edu Lobo, and other guitar-based MPB Proper figures

Pick a genre, or era of Brazilian pop music, and you’ll find a guitar-based melody. There are exceptions, of course. One thinks of the piano-based Bossa Nova of João Donato and Sérgio Mendes, the lite Bossa Nova organ of Walter Wanderley, and the jazz percussionists like Airto Moreiro, and Dom Um Romão. But it is the guitar that dominates the music.

Here’s a live performance of Bossa Nova’s guitar king, Baden Powell

As an introduction of the world of Brazilian guitar, I’ve created a playlist featuring Cartola’s Samba, Garoto’s Choro, the Bossa Nova of Luiz Bonfá, Baden Powell, and Rosinha De Valença, Waltel Branco’s funk, Arthur Verocai’s experimental pop, and Egberto Gismonti’s jazz.

Bossa Nova

If there is a key figure and year around which Bosso Nova pivots, it’s Antônio Carlos Jobim (aka “Tom,” “Jobim”), and 1959. Jobim is responsible for at least a half-dozen of the world’s most recognizable pop tunes (with his frequent lyricist Vinicius de Moraes)

You may have never once owned any Jobim music, or even tried to consciously listen to Jobim on any format, in any context, and yet you will know these songs. They are surely ingrained in your melodic memory.

In 1959, two musical events changed the course of pop music in Brazil. Jobim figured prominently in both events:

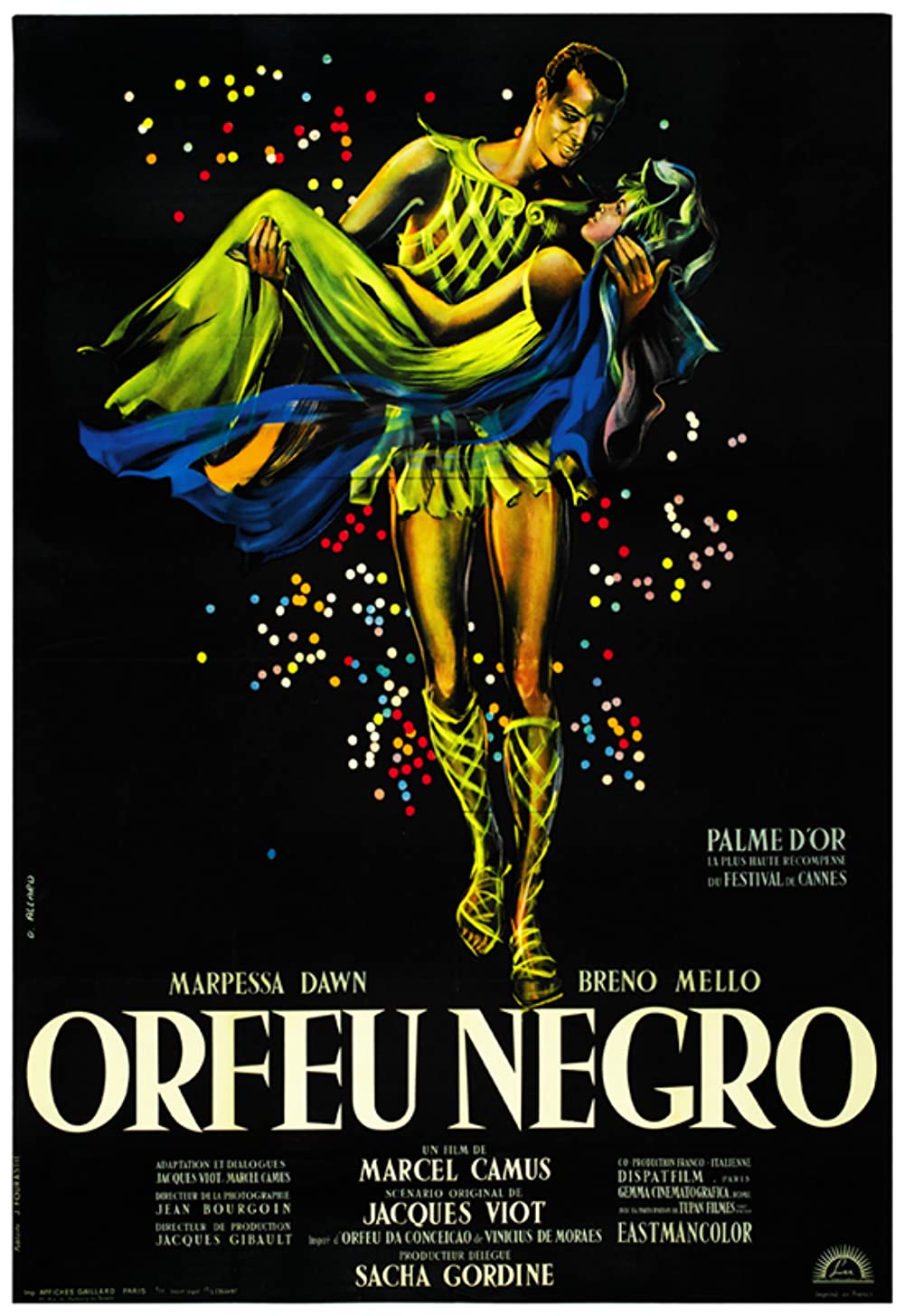

- Marcel Camus’ film Black Orpheus featuring compositions by Jobim and Luiz Bonfá, particularly Jobim’s “A felicidade,” and Bonfá’s “Manha de Carnaval.”

- João Gilberto releases his debut album “Chega de Saudade” featuring several important Jobim compositions, particularly the title track and Desfinado.

For the next 8 years Bossa Nova will dominate Brazilian, and indeed international, pop music. The American musician Gary McFarland in his 1965 album “Soft Samba” perfectly describes the genre with its tranquil, soft, simplified Samba melodies and arrangements, and its repetitive “zhzzz, zhzzz, zhzzz…” and “bah, bah, bah…” vocalizations.

But, Bossa Nova is more than simply the chill Latin sounds of the 1960s wafting sweet dreams of endless beaches, Summer nights and beautiful, girls purring “bah, bah, dubba da, bah, bah…” sounds.

Starting from the beginning, Bossa Nova has always been more radical than cultural memory allows. The opening scene of Marcel Camus’ Black Orpheus, which introduces Jobim’s “A felicidade,” juxtaposes the soft, plaintive Bossa Nova melody against a backdrop of vibrant Samba rhythms as scenes of everyday life in Rio play out. In this context, the song works less as an invitation to a life of plenitude and easy pleasure, than to show up the reality undergirding the vibrant party life of the Samba, the Carnival. The song is contemplative, morose. A song called “happiness,” that is about anything but. The lyrics run: “Tristeza não tem fim. Felicidade sim” [“Sadness has no ending. Happiness does”] and laments the fading pleasures of the poor, who work all year, at carnival’s end, when the illusion subsides and reality returns.

The longevity of Bossa Nova is attested to by the fact that arguably two of its best album’s, João Gilberto’s 1973 self-titled, and Jobim and Elis Regina’s 1974 “Elis & Tom,” were released at the eclipse of Tropicalia.

I’ve created an introductory playlist for Bossa Nova that straddles the classics of the genre, particularly Jobim, Joao and Astrud Gilberto and their various collaborators (Stan Getz, Walter Wanderley), Sérgio Mendes, Joao Donato, Marcos Valle… but also more experimental figures like Edu Lobo, and Tamba 4. Finally the playlist ends with the ultimate crossover figure Jorge Ben Jor, a guitarist that straddles Bossa Nova, Tropicalia, and MPB with aplomb.

Tropicalia

By 1967, living under a military dictatorship since 1964, the tranquil sounds of Bossa Nova hit different. Brazilian musicians, in part taking inspiration from the psych-, garage-, prog-, etc. rock movements, looked to create something new and so launched Tropicalia.

The keystone of Tropicalia, released in 1968, is the unique collaboration album “Tropicália: ou Panis et Circencis.” “Tropicalia, or Bread and Circuses,” an illusion to the Roman spectacles, offers another revolutionary take on the Carnival. Arranged by Rogerio Duprat, the album features Gilberto Gil, Caetano Veloso, Tom Zé, Gal Costa, and Os Mutantes.

Like all Tropicalia albums, this album features melodies that refuse to stabilize. There’s a certain creative anarchy to Tropicalia that puts it closer to the Marx Brothers than the Bossa Nova of earlier Brazilian pop or the rock n’ roll of the Rolling Stones.

Appropriately, I’ve started my introductory Tropicalia playlist with Jorge Ben to help dramatize both the continuity and change from Bossa Nova, even within a single artist. Unfortunately, Ben’s 1970 album “Fôrça Bruta” is missing from Spotify, but you can find it here

The playlist surely stretches Tropicalia beyond the tastes of strict disciplinarians. I don’t provide a firm cutoff between Tropicalia and MPB for a few of artists, particularly Jorge Ben, Gilberto Gil, and Caetano Veloso. Somewhere in the mid-1970s all steer away from Tropicalia and embrace the broad pop sensibility of MPB.

Música popular brasileira (MPB)

MPB gets a bad rap for being yet another 1970s national music that unironically blends the softer edges of popular AM radio friendly music together. Take the lavishly produced song “Davy” from Sérgio Mendes’ 1974 album “Sérgio Mendes (AKA I Believe).” Listen closely and you can hear the cuíca (a Brazilian percussion instrument that creates a funny little laughing monkey sound) chime in at 3:15 mark as a nice nod to the past.

Or, take a listen to former Bossa Nova star Marcos Valle’s lite-disco infused 1983 hit “Estrelar”

But, as mentioned in the intro above, MPB, while certainly broad enough of a genre to incorporate this kind of radio-ready pop, is incredibly eclectic and creative.

Again, I’ve started my introduction to MPB with Jorge Ben to anchor the continuity and transition of the genres. You’ll find a wide range of musical styles here, from the Soul Rock of Tim Maia, to the Jazz Funk of Azymuth, and everything in between.

Thanks for reading and listening!

Here’s a giant playlist consisting of all the tunes from the 4 focused playlists above:

I’ll be further exploring Brazilian pop music all Summer on my Twitter account: @RomulusNotNuma

I would also encourage you to check out last year’s Summer entry on Krautrock

And, the year prior’s on Hard Bop:

And, my twitter thread from the Summer prior on Synth Pop: